Beginning on August 25, 1835 (the year of Halley’s Comet), New York Sun editor Richard Adams Locke ran a series of six articles about the discovery of “man-bats” on the moon.

The articles were said to contain reprinted material from the Edinburgh Journal of Science. The byline read “Dr. Andrew Grant,” who was mentioned as being a colleague of the real-life astronomer Sir John Herschel.

As the cultural historian and poet Kevin Young notes, the appeal of the series was both the intrigue of extraterrestrial life as well as the social organization of different species found on the moon. These observations lent legitimacy to the hierarchized class and race-bound society that existed on earth, which marginalized the poor and people of color.

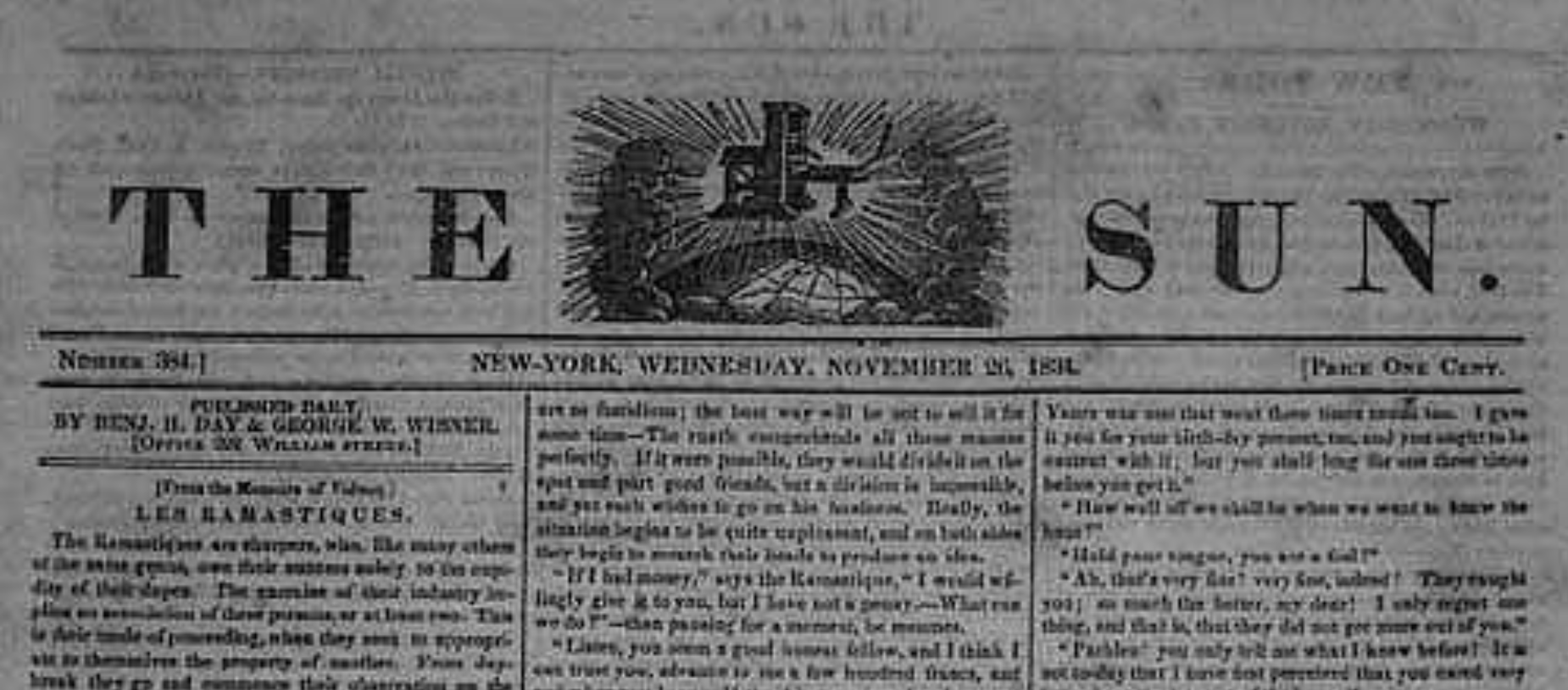

The popularity of the series helped boost the New York Sun’s circulation to 20,000 copies per year. More broadly, the Great Moon Hoax drove interest in the “penny press.” In contrast to more partisan newspapers backed by political parties, this new form of journalism would cost less, rely on advertising and wide circulation, and aim to engage readers through sensational stories about topical events.

References Kevin Young, Bunk: The Rise of Hoaxes, Humbug, Plagiarists, Phonies, Post-Facts, and Fake News (Minneapolis: Graywolf Press, 2017), 12-26. Kevin Young, “Moon Shot: Race, a Hoax and the Birth of Fake News,” New Yorker, October 21, 2017. Photo credits: Font page of The New York Sun, August 25, 1835. The Museum of Hoaxes, http://hoaxes.org/archive/permalink/the_great_moon_hoax. Background theme image, Benjamin Henry Day, “Lunar animals and other objects discovered by Sir John Herschel…” for The New York Sun, 1835, Lithograph, Library of Congress: https://www.loc.gov/resource/pga.02667/.