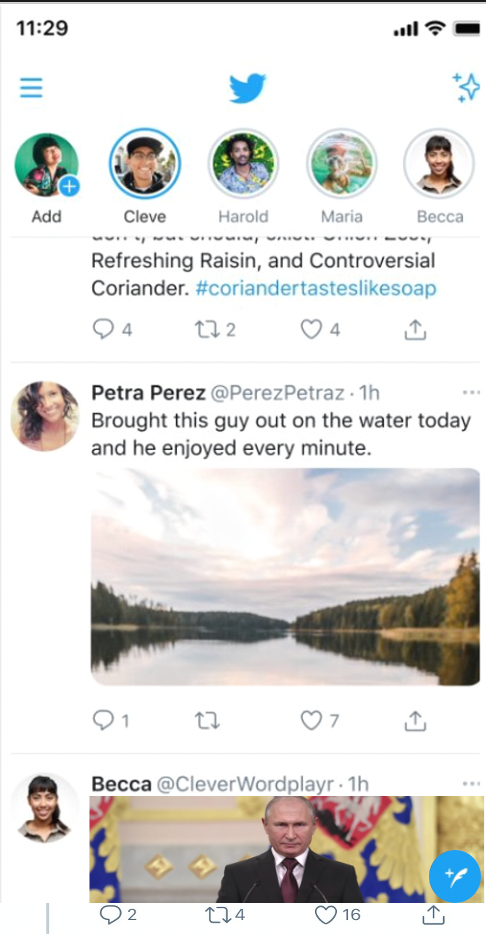

If you encounter a video of Russian President Vladimir Putin in your Twitter feed and his claims seem particularly outlandish, stop and think:

- Does the video have a clearly stated author?

- What is the URL and who is the host?

- What seems to be the aims of the person, organization, or company responsible for the video? What else have they made? Do they have a mission or vision statement? Do they adhere to a set of guidelines or protocols for journalistic practice, scholarly inquiry, or scientific research?

- Do you see the video elsewhere on the Internet, and if so, in what context?

- Are there sources that corroborate what you are seeing and hearing?

These questions might not lead to a clear and definitive answer as to whether the content of the video is necessarily true or false. They are designed to discourage the fast circulation of, and promote a more deliberate reflection on, the media we encounter. More research might very well be needed to determine the credibility of a particular form of media as well as the motivation and intention for making it. These questions are part of a process of critical interpretation and understanding. They should be explored in collaboration with your peers and teacher.

Reference for more on these media literacy protocols and techniques, see Sam Gregory, Witness Media Lab, discussion of First Draft’s SHEEP framework (Source, History, Evidence, Emotion, Pictures). Or, the SIFT framework: https://lab.witness.org/backgrounder-deepfakes-in-2021/. Also, see, Center for Media Literacy, the National Association for Media Literacy Education, UNESCO’s Communication and Information initiative, and communication scholar Pat Aufderheide’s 1993 white paper from the Aspen Institute: Media Literacy – A Report of the National Leadership Conference on Media Literacy. For more contemporary, project-based approaches to media literacy, see Paul Mihailidis, Civic Media Literacies: Re-Imagining Human Connection in an Age of Digital Abundance (New York: Routledge, 2018).